Whole Life Yoga Blog

Lessons from India – Insight at the Coconut Stand

This is one of the things I love in India, the beauty of the people, the authenticity with which people do their work. For example, one time in my early years in Mysore I needed a button sewing on a shirt. I had no needle or thread but I knew there was a tailor around the corner. I took my shirt to him. He looked at me like I was some brutish fool and indicated that I should go up the street. He was a tailor of women’s clothing, and he was not about to desecrate his self-respect by robbing custom from a gents’ tailor.

Whole Life Yoga Immersion: Review

You can recognize a good yoga workshop by the fact that its effect gradually matures in you. That's why I’ve waited until now to give my review of YOGA IMMERSION.If I had to choose one word that...

On Truth and Trauma – with reference to the Yoga Sūtra

Atha yogānuśāsanam - and now ensues yoga. So begins the Yoga Sūtra. What does yoga ensue from? From the knowing that we do not know, from the acknowledging that we are partially (and significantly)...

Yoga Immersion Q&A

Q. What brought you into yoga? A. There are many ways that I could answer this and I could write or speak at length, but to get to the heart of it: pain and desire. I was in pain, I’m a wounded...

Rehab Recipe: Yogic Movement

I sometimes say there is no such thing as merely physical yoga practice, or merely intellectual or devotional practice. If it’s yoga then it will be addressing the whole human being. Yogāsana...

Put Down The iPhone, Get Off The Bandwagon! Eight Yoga ‘Tips’

I was recently asked, ‘What’s one piece of advice you would give to someone just starting their yoga journey?’ I didn’t limit it to one thing, but offered thoughts along these lines. Forget about...

Weddings and Funerals Are Not Enough: On Celebration and Gathering

Last weekend I had the joyful experience of attending my sister’s wedding. It was a beautiful day celebrating her partnership and family, and gathering many of her wider family and beloved friends...

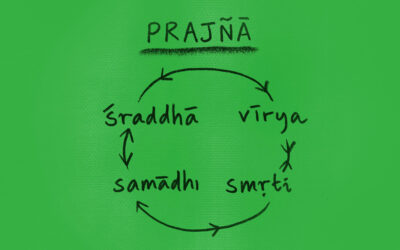

Practical Patañjali – March 2022

Usually when I write about the Yoga Sūtra, it is with commentary and fairly extensive illustration. When I speak about the Yoga Sūtra, I often describe the sūtra-s as being like lighthouses that...

Beyond the Bright Lights

In a recent interview on the Joe Rogan experience, Sadhguru pointed out that a main reason for our human problems is because we have got into deep grooves of searching for...

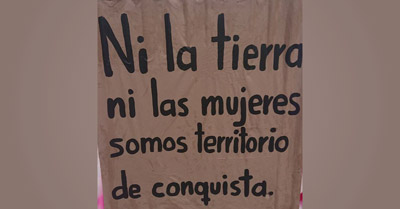

Responsibility and The Invitation

When we try to dominate another, we are at once denying, attacking and suppressing part of ourselves. Brother, sister, you too are Mother Earth.When a human being tries to dominate another, or tries...

Yoga is a Four Letter Word – a Few More Introductory Thoughts

‘Satyam eva jayate’ - truth alone prevails - so it is stated in the Mahābhārata epic. Truth and truthfulness are at the heart of the Indian tradition, and are the life pulse of yoga, the practical...

Killing Me Softly

I heard he sang a good song, I heard he had a styleAnd so I came to see him, and listen for a whileAnd there he was this young one, stranger to my eyesStrumming my pain with his fingersSinging my...